There’s a lot of information floating around out there about attention spans. Some sources cite that humans have an attention span that’s less than that of a goldfish. Others say we can’t expect audience members to listen much past the 10 to 15-minute mark. And the TED organization asks its speakers to stay under 18 minutes. You don’t have to spend much time on the internet to see these or similar statistics repeated.

But What Does Research Actually Say About Attention Span?

As I tried to find the source of these suggestions, I didn’t have much luck. And it turns out I’m not alone. Experts have tried to trace these stats back to solid data without finding anything of real substance. Both the BBC article “Busting the Attention Span Myth” and an article in the academic journal Advances in Physiology Education tell of their own journeys to pin down these oft-repeated stats. They’ve proven that no one really has much solid, scientific evidence that attention span naturally drops after a certain length of time. And the studies that are out there use unreliable data collection methods for measuring attention span. Things like notetaking, self-reporting with clickers, and observation.

That doesn’t mean we should drone on and on in our presentations. But it does mean that, as of yet, there isn’t some specific length you can make your presentation that will ensure your audience doesn’t lose focus. It also means that if you are spending a lot of time trying to fall within a certain time frame that you’ve seen broadcasted on the web as the magic number, your attention and effort might be better directed elsewhere. Which brings us to another important point when discussing attention span.

Are We On a Downward Spiral?

I’ve heard speakers talk about the attention span of audience members in an incredibly negative way. They seem to think they are fighting a losing battle no matter what their presentation strategies are. Maybe they talk about things like a hurried pace of life or technology like smartphones as if they were nails in the coffin of the human attention span. Or they quote statistics about how quickly people jump from webpage to webpage (which is a matter of seconds), handing out hopelessness like doomsday preachers.

But wait. What if we aren’t at the top of some slippery slope that leads to a point of no return when it comes to attention? What if we are comparing apples to oranges? We know that humans consume information differently in different scenarios. We look for information on the web differently from how we listen to information in a presentation. So the statistics about one certainly aren’t directly transferrable to the other. Which I hope brings you a little bit of peace. Just because we can consume information more quickly, and often do, doesn’t mean we aren’t able to still focus for longer amounts of time. Which brings me to the next question.

Whose Responsibility Is It?

Some of the discussion around attention span has to do with whether the speaker or the audience is responsible for gaining or maintaining attention. Honestly, it’s both. Sure, some of the responsibility falls on the audience to listen. To minimize distractions. And to bring the best of their focus to the presentation.

But not all of the responsibility falls on the audience. Which means we can’t jump on the downward spiral bandwagon. Because if we do, we might start to feel like there is nothing we can do to keep our audience’s attention. And that’s simply not true. In fact, Neil A. Bradbury looked into modern day attention spans and whether lecturing is still a valid method of relaying information. He says that “at least two factors can be associated with attention: arousal and motivation.” He goes on to say, “Certainly charisma helps in generating excitement about a subject in students, but probably the biggest aspect of inspiring students is passion for the subject on the part of the teacher.”

If that’s true, and I happen to believe it is, it’s time to roll up our sleeves and get to work. Because what we do as presenters makes all the difference when it comes to audience attention.

What Can We Do To Gain Attention?

Bradbury says it comes down to passion and motivation. Let’s start with passion. In The Passionate Learner, Robert L. Fried says, “More than knowledge of subject matter. More than variety of teaching techniques. More than being well organized or friendly or funny or fair. Passion. Passionate people are the ones who make a difference in our lives.”

Which leads me to ask, are you passionate about the subject of your presentation? If not, that’s a problem. One that no amount of organization or practice is going to make up for. One which you need to solve before you ever step foot in front of your audience members. If you find yourself lacking passion for your subject, spend some time asking yourself these questions:

- Why is what I share important?

- Has my life changed because of the information I’m sharing? How so?

- How could my audience members’ lives change for the better because of my presentation?

- What gifts does this presentation/subject offer to others? (Efficiency, clarity, economic savings, knowledge, a new perspective, etc.) And why do those things matter?

After you’ve taken some time to rekindle your passion for your presentation, it’s time to get the audience motivated. The good news is that your passion will usually come across so it will be naturally contagious for your audience. But if you worry that they’ll need a bit more influence, think about what motivates them.

Don’t expect that your audience will do the work to figure out why they should listen to your presentation beyond polite social pressure. You have to spell it out for them by reminding them of the relevance it has in their lives.

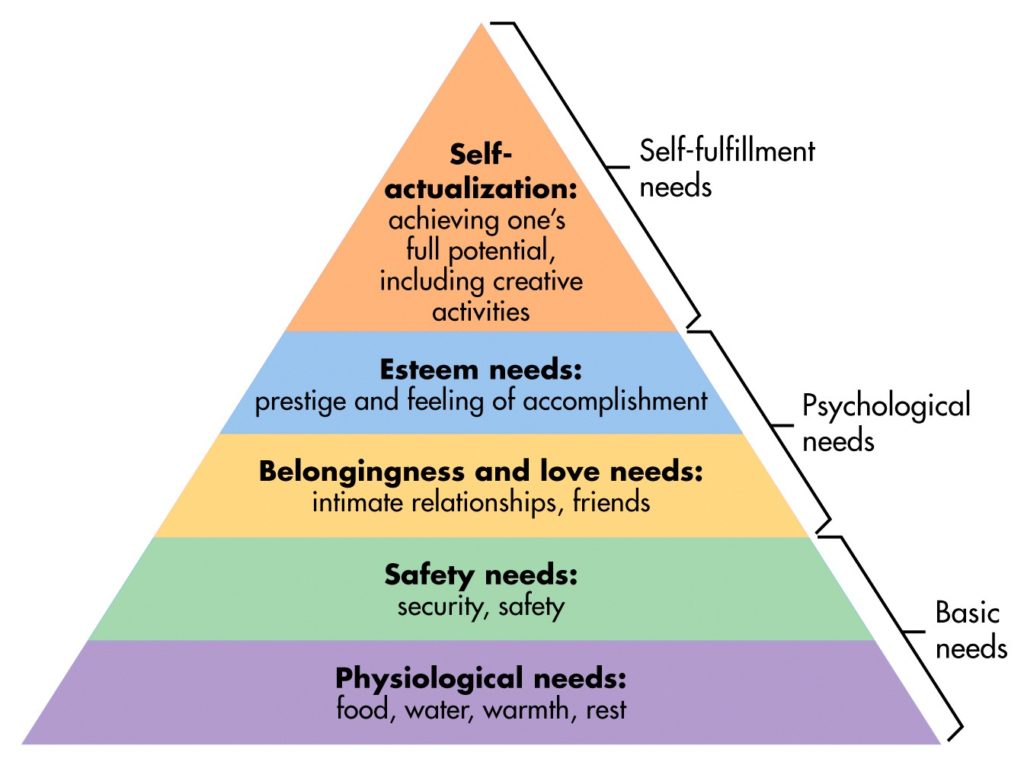

It might be a good time to refresh your memory on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, a great tool for understanding what motivates humans.

Show how your presentation intersects with and meets the needs of your audience. For example, maybe you are pitching a productivity app that allows workflow to be more efficient. You might appeal to belonging needs by saying the app can make more time for the audience to spend with friends and family. Or you might pitch the same app by appealing to self-fulfillment needs with a statement like this, “imagine how much more you could accomplish with 30 minutes more in your workday.”

When you show how your presentation meets needs, your audience is motivated to pay attention.

Summing Up Our Attention Span

So here’s the lowdown on attention span. To start, we don’t have to worry; we aren’t turning into distracted humans with attention spans less than that of goldfish. And we don’t have to believe that length of presentation is the main factor in audience attention span. Science has yet to prove that’s the case. But we do know that it’s partly our responsibility to create presentations worthy of our audience’s attention. And when we present with passion and we work to motivate our audiences through specific and relevant appeals, we can make that happen.

Ready to get started on your next big presentation? We can help.